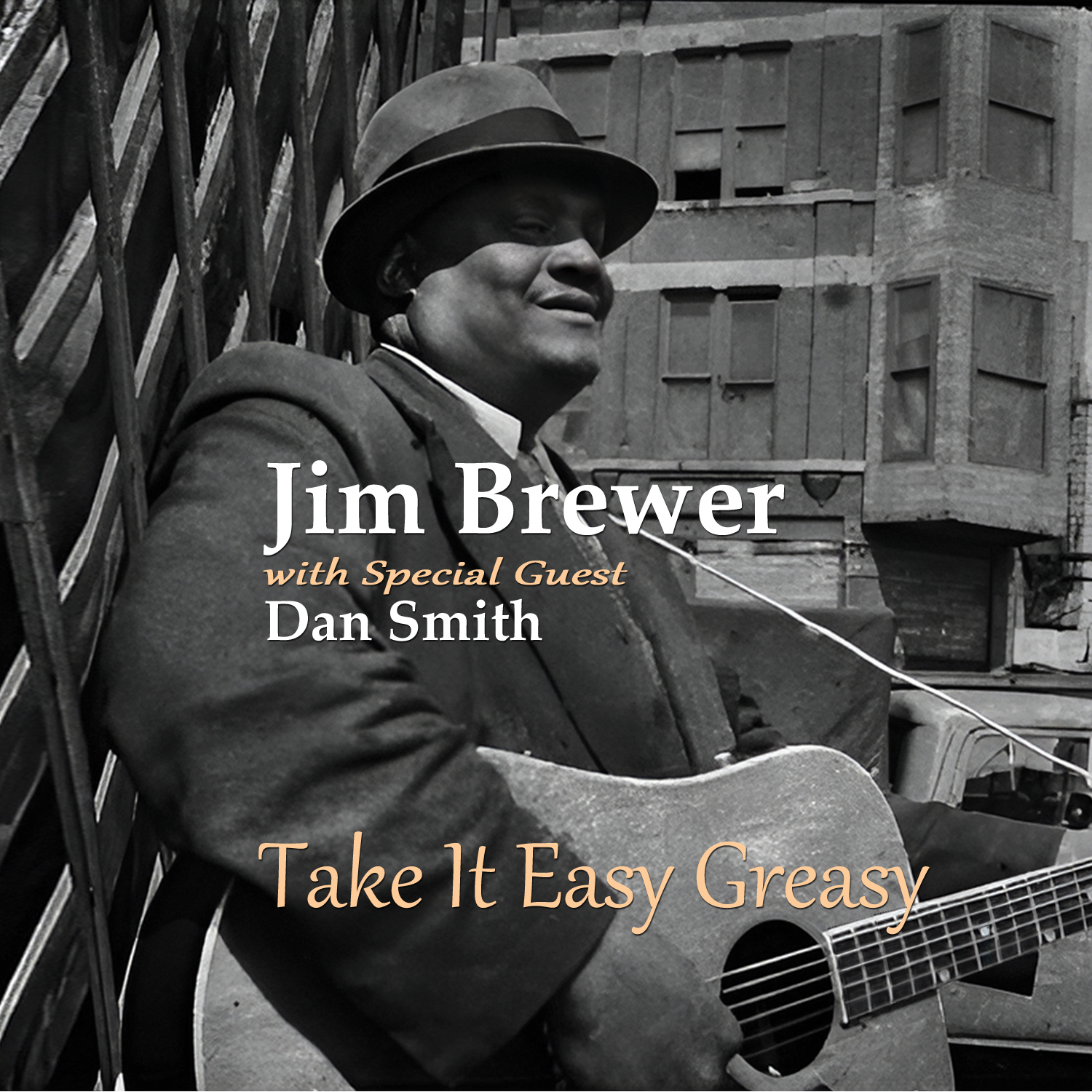

Take It Easy Greasy – Jim Brewer with Special Guest Dan Smith

$14.99

Take It Easy Greasy presents two Folk-Blues and Gospel masters from the old days, Jim Brewer and Dan Smith, with all songs remixed and mastered.

Description

Jim Brewer (1920-1988) – acoustic, guitar, autoharp and vocals and Rev. Dan Smith (1911-1994) – harmonica and vocals. Assembled from concert and studio recordings, this is a compendium of ‘Folk’ Blues and Gospel songs mixed with covers of Blues 78s dating back to Jim’s teenage years. This is the first time these songs have been issued, though the tapes date from 1966 to 1984. On the several numbers they play together, Dan sings and plays harmonica, and Jim backs him on autoharp.

CREDITS

Album produced by Andy Cohen and Michael Robert Frank

Tracks 1,15 January through March 1978, produced and recorded at Reel Recording Company, DeKalb, IL by Mark Leach and Jeff Meier

Tracks 2,3,4,5,6 recorded at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI July 29, 1984, engineer unknown

Tracks 7,8,9,10,11,16 recorded by Bill Fonvielle at an Evanston, IL, House concert, May 13, 1966

Tracks 12,13,14 recorded at the Gentry Remedy Company, Bloomington, IN, November 15, 1980 by Bruce Conforth and David A. Brose

Songs 1,2,3 traditional, new words, music & arrangement by J. W. Brewer

Songs 9,10,11,16 written by J.W. Brewer, Earwig Music

Song 7 written by Fulton Allen, BMG Platinum Songs US

Songs 4,5,6 written by Dan Smith, publisher unknown

Song 8 written by James A. Lane, Arc Music

Song 12 written by Hudson Whittaker, Wabash Music Company / Songs of Universal

Song 13 written by Sam Theard, Jay Mayo Williams Music

Song 14 written by Hudson Whittaker, publisher unknown

Song 15 written by Gertrude Ma Rainey & Lena Arant, Universal Music Corp.

Mixing, editing and mastering by Jim Godsey, JBG Audio, Palatine, IL

Liner Notes written by Andy Cohen and Michael Frank

Graphic design by Steven Hausheer

Front Cover photograph by George Mitchell

©℗ 2025 Earwig Music Company. Inc. and Riverlark Music, LLC.

TRACK LIST

- Jim’s Highway 61 4:16

- Corinna Corinna 2:14

- Crawdad Hole 1:59

- The Train 2:43

- Cotton Needs Pickin’ 3:23

- Babylon Is Falling Down 4:25

- Step It Up and Go 3:22

- That’s Alright 3:59

- Must I Go or Stay 3:47

- Oak Top Boogie 3:00

- Jim Brewer’s Talkin’ Blues 5:10

- Don’t You Lie to Me 2:45

- What You Gonna Do 2:44

- It Hurts Me Too 3:04

- See See Rider 3:20

- Tell Me Mama 5:16

Liner Notes by Andy Cohen and Michael Frank

I met Jim Brewer when I was a college student in 1965, when I wandered into a dance he was playing at the University of Illinois-Champaign. His friend / student Albert Hollins had driven him to Champaign, Illinois to play a dance at the McKinley Foundation, the Presbyterian enclave on the campus. I was nineteen and had seen and heard some blues players already. Jim was obviously among the best: fluent, ready, unhesitating, into his job of being an entertainer. One of the things that distinguished him was that he was all over the fingerboard with all four of his left-hand fingers, using ‘thumb-over’ chords rather than barre chords. Jim could see a little but was legally blind; I took him for one of those legendary Mississippi players, and I was right. He was fast and his execution was clean. I considered him in the same category as other great players like Rev. Gary Davis and Willie McTell, whose blindness enhanced their hearing and expertise on their instruments.

Jim was from Brookhaven, Mississippi, along with Little Brother Montgomery and a few other blues players who ended up in Chicago. The Stripling Brothers, a champion fiddle-guitar duet, were also from there, and Jim was no stranger to what we now call Old Time Music. Born severely visually impaired, one of his eyes had been removed when he was about seven. His parents couldn’t send him to a school for the blind, so they trained him in music. His dad was a barber and avocational blues singer and guitarist; his mom was a singer of religious songs. They argued over whether he should play Blues or Gospel on the street. ‘How could you be hurt by a song?’ Jim reasoned and did both as needed.

His repertoire was largely derived from records, local players and encounters with traveling bluesmen. He could make things up too, composing songs out of fragments like everyone else. He was exposed to enough Old-Time music to please most anybody. He took to his father’s teaching and picked enough music up out of the air to become known and admired in his own neighborhood and across the color line. He described a situation where some cops were giving him a hard time and the white folks nearby came to his defense and vouched for him.

His family left for Chicago in 1940. Jim followed about six months later and soon gravitated to Maxwell Street, an open-air bazaar that covered six square blocks down below Roosevelt Road. There he established himself as both a Blues and Gospel player, often backing up an energetic preacher woman named Sister Carrie. She would beat a tambourine while she sang Gospel songs from some far-off down-home place, while stepping and jumping around without ever crossing her feet.

Jim was intelligent, a tinkerer, observant and keen. Maxwell Street was kind to him, jumping with crowds, commerce and lots of musicians playing on the streets for tips. He played there most Sundays for forty-eight years. He cherished his independence, sight or no sight, and bridled when ‘Blind’ was applied to his name. “My mother named me Jim. She didn’t name me ‘Blind’”. Much of Jim’s world was Maxwell Street. He could get tools or instruments there as he needed. Many blues and Gospel people played there, and Jim had many friends among them: Albert Hollins, Daddy Stovepipe, Arthur Crudup, Robert Nighthawk, Maxwell Street Jimmy, Arvella Grey, and a washboard player named Pork Chop.

In the early 1960’s, college students started coming to Maxwell Street, and they recognized Jim as a sort of ‘Little Big Bill Broonzy’. He got hired at places like the University of Chicago Folk Festival, Juicy John Pink’s out in DeKalb, and sometimes all the way to Madison, Wisconsin. Sometime in the mid-sixties Joe Moore hired him to play every Wednesday at his No Exit coffeehouse on the North Side of Chicago. Jim kept that job for more than twenty years. Jim was the Maxwell Street virtuoso! He taught Arvella Grey, his friend Albert Hollins, and exchanged licks with Honeyboy Edwards and John Dee Holeman in my presence. ‘Didja get that lick’; “yeah, I got it’.

Jim recorded scattered tracks between 1960 and 1964 on a variety of compilations for several labels but had no album of his own. He made his first album, Jim Brewer, for Vermont label Philo Records, in 1974. He made his second album, Tough Luck, for Earwig Music Company in 1984, a combination of concert and studio tracks from 1978, 1980 and 1982.

In 1971, Jim and Fanny suffered a home invasion that resulted in Jim losing the distal part of his left little finger. Jim continued playing; the damaged finger got in the way of his formerly clean technique. It slowed him down some, but didn’t stop him, because playing music is minded behavior, independent of the condition of the body. Nevertheless, he continued playing all the places he had before and added a bunch of folk festivals to his résumé in the process.

In 1972 Jim met blues fan Michael Frank in a Chicago Club, and within a few years had Michael managing his career. Jim introduced Michael to me around 1973. Michael and I together and separately arranged gigs for Jim at clubs, concert halls, folk and blues festivals between 1974 and 1988, when he passed. Jim died of a heart attack at home in Chicago, June 2, 1988.

I’m not exactly sure where I met Dan Smith, probably at the 1970 Fox Hollow Festival when I was living in Saratoga Springs NY. Café Lena took advantage of Dan and Bessie Jones being nearby and booked a special weekend with them, for which I was drafted to play backup guitar. Dan was from Purdue Hill, Alabama, born in 1911. His mom had several kids from a previous marriage; his dad, who Dan said was a good man and a good provider, was a river man sometimes, a railroad man sometimes, and a farmer sometimes. He died from injuries he suffered after a fall from a railroad trestle.

Dan’s description of his childhood is nothing short of tragic, but he survived it, even as his older siblings came and went. In a handwritten biography he tells of the kinds of farm labor he did from the age of four until he started ‘working out’ at fifteen. He too labored at jobs on the river and on the railroad until he found consistent work in the turpentine industry. A big man, Dan was tasked with tapping three stands of a hundred trees each, four taps to a tree, pouring it in the barrel and taking it to the turpentine plant in a horse-drawn wagon. In 1943 he emigrated North to work at the Chrysler plant in Tarrytown, New York, for actual wages. He was the guy at the end of the line with a

pressure hose, washing the acid off the new engine blocks after they were dipped. The acid ate his lenses, taking away his sight and with it, his work.

Through all these travails he played the harmonica, sang in church choirs and with friends. He credited the music and Jesus with helping him carry on through an otherwise difficult

existence. At times he was so poor he couldn’t afford a fifteen-cent harmonica, only a comb and tissue paper. Once he moved up North, he earned a regular worker’s wages; and when he had to retire because of his sight, he got some benefits. He had become close to the Seeger family during the 1960s and sang at many of the local festivals like the Clearwater and Old Songs gatherings. He had sung with the Georgia Sea Island Singers at times, was familiar with a whole range of play-parties, spirituals, and Gospel songs of his own and others’ making. And like so many players, he whipped up some remarkable harmonica instrumentals.

Our Impetus for Producing This Album

In 1983 I broached the idea to Michael of a traveling Blues festival, self-contained in a Winnebago. I thought I could book it across the country and back. Eight months later Michael called and said ‘Start bookin’! I just inherited my mom and stepfather’s Winnebago! I booked the Winnipeg and Vancouver festivals, and gigs in Oregon, Minnesota and Wisconsin. The Revue consisted of me, Fris Holloway and John Dee Holeman from North Carolina; Jim Brewer, Dan Smith from New York, a Chicago band made up of Kansas City Red (Arthur Lee Stevenson), Honeyboy Edwards, Lester Davenport and Michael Frank, plus Frank Frost from Mississippi. Off we went, with Frank Frost dealing seconds to Fris, John Dee and Kansas City Red in a continuous game of Tonk. We counted ourselves lucky to have a preacher with us. All of us called Dan “Rev”.

I would start the show, Fris and John Dee would be up next and then we put Jim and Dan on together. The band played last. What wonderful pairings they all were. They played together like they were born to it, which they were. Though all the Traveling Blues Revue musicians played great, Michael and I wanted to spotlight Jim and Dan on this album. They loved playing together, and Jim surprised us by bringing an autoharp with him on the tour, using it to back Dan’s magnificent harmonica playing and huge baritone voice. After the tour ended, we were able to get them together a few more times. We also did two pared down Traveling Blues Revues in 1985.

After that, Michael kept on booking and managing Jim’s career and Honeyboy Edwards’. I went back to touring on the traditional folk and blues circuit. Jim died in 1988 with gigs on his calendar; Dan carried on until 1994. Michael and Honeyboy continued to tour and record until Honeyboy died August 29, 2011. Michael and I are the last of that band of musicians. Now both Michael and I have our own record labels, Earwig Music Company and Riverlark Music respectively, and we continue to work with musicians young and old who play the old tunes.

In the years since Jim’s and Dan’s passing, Michael and I looked for an opportunity to release a historical album of them together. When Bill Fonvielle contacted us in 2021 about the 1966 house concert tapes, that gave us the opportunity. In keeping with one of Jim Brewer’s favorite sayings, “Take it easy, Greasy, we got a long way to slide”, we titled this album Take It Easy Greasy.

Jim Brewer 1966 House Concert

Bill Fonvielle was a college student at Northwestern University in Evanston Illinois in 1966 when he heard Chicago street singer Jim Brewer at a Northwestern Folk Festival. Bill loved Jim’s set. Soon thereafter, one of Bill’s roommates joined the Army Reserve and got shipped out to Alaska, leaving Bill and his remaining roommate short on the rent. So these enterprising guys decided to throw a rent party and hired Jim Brewer to play it. Bill plastered the street with posters, packing their apartment with gregarious young folks eager to dig some blues and drink beer on tap, all for $1.00 admission and $1.00 beer. They made their rent and then some. However, Bill and his friends did not stay in touch with Jim afterwards or see him play again. Fortuitously for Earwig Music and fans of traditional blues, Bill used his portable tape deck and two microphones to record Jim’s two sets. Fast forward fifty-five years to 2021, and Bill, now living in Massachusetts, told his friend Gary Leopold about his tapes of Jim and the house concert. Gary, who worked with veterans making music, got the tapes digitally transferred and searched on the internet for information about Jim Brewer. Gary reached out to Earwig Music Company after discovering that Jim Brewer had recorded for Earwig in the 1980s and that Michael Frank, Earwig owner, had managed Jim’s career.

Excited to hear that recording of Jim in his prime, Michael struck a deal with Bill Fonvielle to release eleven tracks on the Earwig Music label. This album has six of those tracks and the digital release includes the other five. This CD was made from four separate sources, 1966 through 1984. The tracks are being released on this album for the first time.

Take It Easy Greasy Song Notes

- Jim’s Highway 61- 4:18 – Played in A, this is probably a recombinant composite of floating blues verses fashioned by Jim over the years. Jim was a big fan of Big Bill Broonzy, you can tell that from his playing. The Greyhound motif ‘with the tongue hangin’ out the side’ appears in other blues songs. In the old days the bus would pick you up if it was going your way, but Jim despairs of it, and there’s gonna be some walkin done.

- Corinna, in C, is a bouncy version of the Mississippi Sheiks hit song of the twenties, the same one that inspired Bob Dylan’s more wistful take on Freewheelin’.

- Crawdad- Everybody knows this one! It’s neither a blues nor a country song, just an old folk song about crawdads ‘cause EVERYBODY likes to eat ‘em. Jimmy Tarleton, who recorded Columbus Stockade Blues in 1925, taught me this verse on the train from Champaign to Chicago in 1965: No more shall I buy my sweet thing pork chops / Watch her lips go flippity flip flip flip flop / Well it’s lip to lip and gum to gum, watch lips smackin’ and a yum yum yum / Goodbye honey if you call that gone I’m leavin’.

- The Train (Dan Smith solo): Every good harmonica player should have a train number in their repertoire. This one is Dan’s, and it’s a doozy.

- Cotton Needs Pickin: Dan grew up doing that, Jim played guitar so he wouldn’t have to. The people in the fields used to sing this among other songs, to help the time pass. This is how it’s supposed to go; the treacly versions that popped up in the 1960s Folk Revival owe some royalties to all those sharecroppers. Jim is playing autoharp on this one and the next one.

- Babylon is Falling Down: ‘The man thought he had it made, but he didn’t have it started’, says Dan about Nebuchadnezzar, the Babylonian emperor who took over Tyre and Judea, the one who brought the population of Jerusalem to Babylon There they lifted their eyes unto the hills, whence came their help.

- Step it Up and Go is a traditional refrain that serves for a million couplets. Jim knew the ones he learned from the Blind Boy Fuller 78, and frequently sang them, but lord knows where he got these verses from. It’s the guitar part and the refrain with Jim’s choice of coupled epithets.

- That’s All Right: Written by James A. Lane, better known as Jimmy Rogers, the Blues player (NOT Jimmie Rodgers the yodeler). Jim played music for about enough money to live on, give or take. He played folk songs, Blues, Gospel and country songs for whatever audience was in front of him. Like every other street singer, he was working for that dime. He was conversant with all the hits in all the different neighborhoods he played in. This CD is sprinkled with such hits from Ma Rainey and Tampa Red and Pine Top Smith, The Mississippi Sheiks, all of whom were popular when Jim was coming up.

- Must I Go or Stay, on the other hand seems to be one of Jim’s own, possibly improvised on the spot (some of the couplets don’t rhyme). Jim mostly played in E, A, G, C, ’plain’ D and ‘Drop’ D, ‘Vestapol’ (open D) and ‘Spanish’ (open G).

- Oak Top Boogie: This is Jim’s version of Pine Top Smith’s Boogie Woogie, done on a guitar after a piano player challenged Jim to do it with his paltry six strings. It pretty much follows Pine Top’s 1938 version, with some variations of his own. Take it easy Greasy, got a LONG way to slide!

- Jim’s Talking Blues: We named it that because Jim backs it on the guitar the whole time he’s telling the story. This is a REAL old joke about an OLD lady that takes a shine to a younger man, which Jim makes hilariously his own- ‘There may be snow on the roof, but there’s still fire in the furnace!’

- Don’t You Lie to Me is a Tampa Red song from about 1938. This is another one that Jim ‘covered’, one that his neighborhood listeners would have wanted to hear. You can hear Jim say ‘Tampa Red!’ as he goes into the instrumental part.

- What You Gonna Do: A silly old song from Jim’s youth: known by many musicians as “Oh Red”. “Oh Red, fell out the bed, bumped his head, then he dropped dead.” This song was written by Sam Theard, and was first recorded by The Harlem Hamfats in 1936 for Decca Records.

- 14. It Hurts Me Too: Styles begin to converge. Here is another Tampa Red song but done smoothly as if it were a country song. It was also a hit for Elmore James with some lyric changes. It’s another song where Jim substitutes his own verses for Tampa Red’s and just keeps the refrain and the guitar part. None of the words are the same as Red’s.

- 15. C. C. Rider owes its popular currency to Ma Rainey’s 1924 version, though it was well known before that. Y’all know what a rider is; the song’s ‘envelope’ is defined by the form and content of the first couple of verses, and Jim’s version follows Ma’s pretty closely. 16. Tell Me Mama (key of G), influenced by Washboard Sam Brown’s version, Jim threw in some verses and comments of his own making. Here is another one of Jim’s originals. Tell me Mama indeed!